Page last updated on: Tuesday, 20 March, 2018.

N.B. holding your mouse pointer over any picture will display the caption for that picture.

The early part of 1914 was just like any other year for Gatehouse. The Town Council were dealing with a usual range of problems :

• the sewage scheme

• cost of re-surfacing High Street with tarmac

• approving a license to show films

• Giulio Frullani was licensed to sell ice cream

Further afield, friction between European countries came and went as was common. Even after Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in the Bosnian capital Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist on 28th June very few people had any idea of what carnage was to follow.

Germany encouraged Austria to retaliate against Serbia, a move opposed by Russia and France. Throughout July, the people of Gatehouse, like compatriots all over Britain, anxiously followed developments on radio and in the newspapers.

Germany declared war on France, and having done so invaded Belgium. Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany to cease its annexation of Belgium and France.

The Post Office in Gatehouse remained open on Sunday 2nd of August, a very unusual event – something was about to happen. The Provost of Gatehouse, Andrew Laurie, had been briefed to expect a telegram which was duly received on Monday 3rd August.

No response was received to Britain’s ultimatum, and as a direct result Britain declared war on Germany as of 4th August, a mere 37 days after the death of Franz Ferdinand, during which time diplomatic proposals seem to have “fallen on deaf ears”.

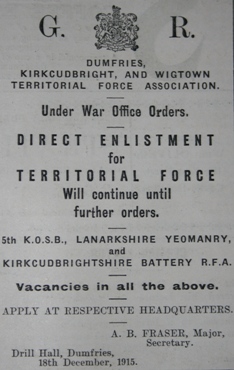

A public meeting was called at the Town Clock at which it was announced that volunteer

s would be required to be trained in readiness for combat.

The general feeling seems to have been that it was just a matter of stopping the German advance into France and that war would be over before the end of the year.

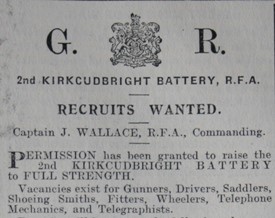

Various groups left Gatehouse immediately, including :

• Col Murray Baillie with the Cavalry Reserve

• Capt. R S Glover with 'H' Company, KOSB

• Sgt. T.H. McGaw with the Gatehouse section of the Royal Field Artillery.

Many of these men had been training with the Galloway Rifles and other territorial units in the period before the war, although most of the men who joined up in 1914 had no real knowledge of warfare.

|

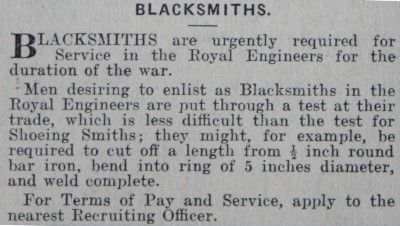

Clearly armed combat needs strong young men who can handle rifles and artillery. But a large number of “fighting men” a long way from home need all the back-up and support of any other local community. Clearly casualties needed nurses and doctors; men were needed to dig and shore-up trenches; food had to be supplied and cooked; equipment and machinery had to be maintained and repaired; many soldiers went to war on horseback and befriended local cats, dogs and other animals – so blacksmiths and vets were needed. The list of talents were considerable. In Gatehouse, the Town Hall was set up as a recruitment office. Men were keen to volunteer. There was a sense of adventure about going to war – young men going away to “prove themselves” with their pals.

|

||

|

|

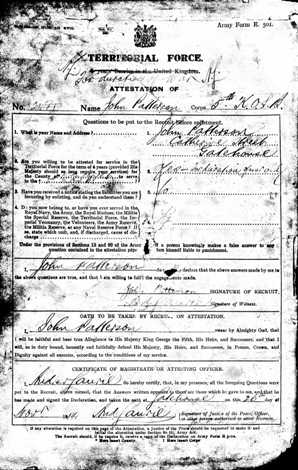

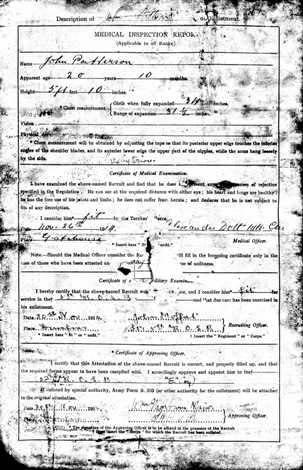

For each volunteer a form was completed giving details of age, height, place of birth, home address and occupation.

They were given a rudimentary medical examination, usually by the local doctor. Dr Dott, the Gatehouse doctor, signed many of the forms. |

|

|

As can be seen, some of these forms are not well preserved. Many were lost completely in a building fire during the 2nd World War, and the condition of many that remain are damaged as can be seen in these 2 examples. |

||

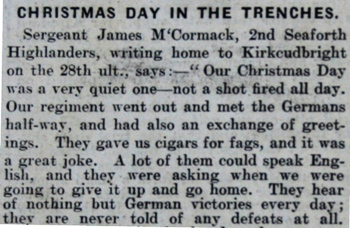

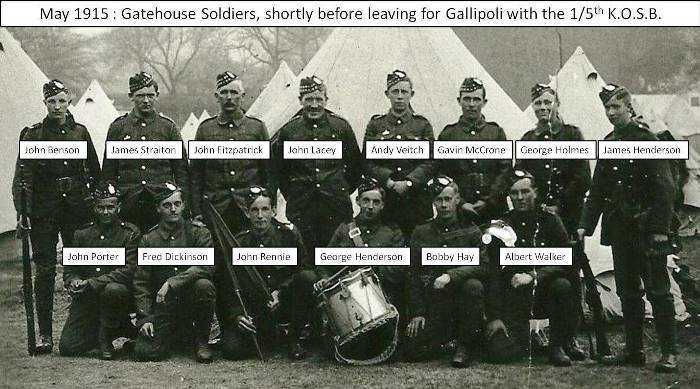

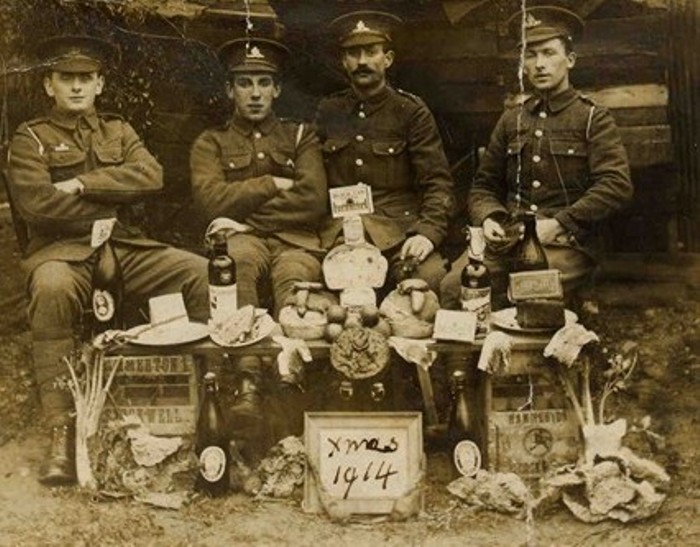

On 25th December 1914 The Kirkcudbrightshire Advertiser published, under the heading Stewartry Roll of Honour, two lists of men who had “gone to war”, one from Gatehouse and one from Anwoth & Girthon. Of the 96 men mentioned, 44 had joined the 5th King’s Own Scottish Borderers, including this group of Gatehouse soldiers.

By the time the War ended around 360 men (and a few women) from the Gatehouse area had served their country.

by Gatehouse servicemen when they first enlisted.

by Gatehouse servicemen when they first enlisted.

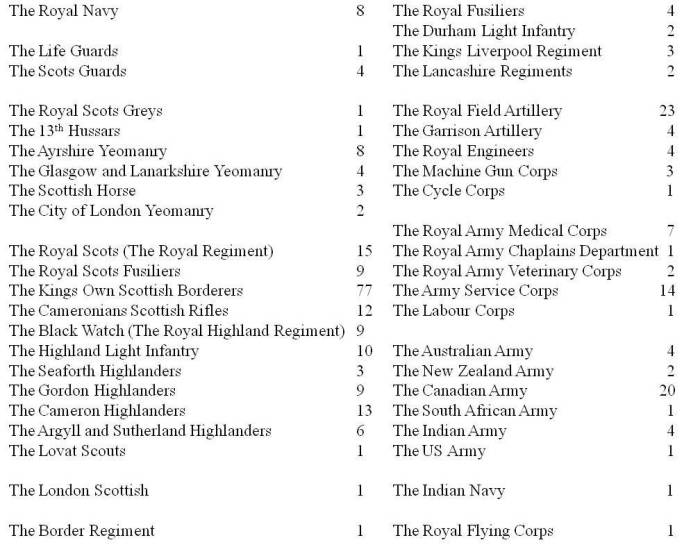

After initial enlistment, new recruits would undergo training, and then it was common practice for men to be posted to other Battalions or Regiments. Much depended on the aptitude of each soldier, but also on where replacements were required for battle casualties. So many soldiers did not end up in the Regiment to which they first enlisted.

Some Gatehouse men joined Regiments elsewhere. The above list involves some 303 names out of about 360 that we know were associated with the Gatehouse area. There are some soldiers for which we have no regiment details. Of the total, 119 lost their lives. This number is greater than the 88 names on the Anwoth & Girthon War Memorial because some soldiers, or their families, had moved away from the area before memorials were erected.

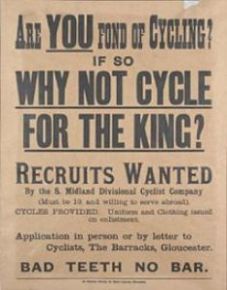

Cyclists Battalions

Several Regiments had Cyclist Battalions, which were largely used for reconnaissance and courier work. Although the bicycles were heavy and difficult to handle over rough muddy ground, they were cheaper and quieter than horses. Each Cycle Corps needed Cycle Artificers (mechanics).

Private James Heron joined the Highland Cyclist Battalion which was part of the Royal Highland Regiment (The Black Watch).

Cycling near the Front Line could be dangerous and indeed James Heron was killed in April 1918 at the Somme. Most Cyclists Battalions were disbanded by the end of the war.

Gatehouse Soldiers Elsewhere

|

|

James McMurray, a postman, was in London and joined the P.O. Rifles, City of London Regiment. Private James McMurray was killed in October 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. William Webster Stark lived in Liverpool and joined the King's Own Liverpool Regiment. William's grandfather William S. Stark had been schoolmaster at Anwoth School. Young William was sent from his home in Liverpool to be educated in Gatehouse. He became a clerk at a biscuit factory in Liverpool. Private William Stark was killed in August 1915 after the Battle of Hooge. |

|

|

Some soldiers had made the army their career choice before the start of war. |

|

|

|

Private William Macaulay had served in India with the Hussars. The Hussars were still in India when William re-enlisted so he joined the Life Guards. He was killed in November 1914 at Ypres, aged 32. |

|

|

|

|

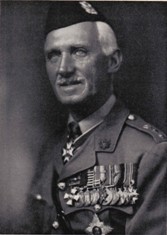

Lieutenant-Colonel Algernon Stewart from Ornockenoch was educated at Sandhurst, and before the war had fought in campaigns in India and Africa with the Seaforth Highlanders.

He was shot by a sniper in May 1916 whilst inspecting the lines in France. |

|

|

|

|

|

James Hunter, clerk of works on the Cally Estate, enlisted with 5th KOSB when he was 47. Like many older men, he was allocated to Home Service in 1916, when he was promoted to Sergeant and transferred to the Royal Defence Corps. He served in one of the Detention Camps for Foreign Nationals on the Isle of Man.

Germans, Austrians and Hungarians who were living in Britain were detained in these camps for the duration of the war.

|

|

After the initial enthusiasm, the number of volunteers reduced significantly and the Government used various tactics to entice more men to enlist. They encouraged groups of men from the same village, workplace or with similar interests to join up together for companionship. Media personalities and sportsmen joined these battalions.

|

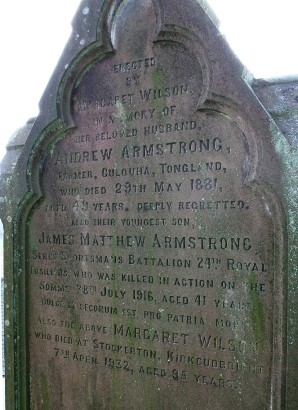

James Armstrong from Culquha, Twynholm joined the 2nd Sportsman's Battalion (24th Royal Fusiliers) in April 1915. Like many in the battalion, he may have been an expert horseman, having spent 10 years as a cattle rancher in Argentina. James was born at Rusco, Anwoth but like many in farming, his family moved around the area. He was killed on 28th July 1916 at Delville Wood, France. His is named on a family gravestone at Balmaclellan and his name appears on the Ringford War Memorial.

|

Thomas and William Nelson, farmers from Gatehouse, emigrated to Ontario, Canada. They both enlisted in the 18th Battalion Canadian Infantry. On 13th September 1915 they were both killed by the same shell. They are buried side by side at Ridge Wood Military Cemetery in Belgium. |

The practice of encouraging friends, relatives and colleagues to fight together was later discouraged because it resulted in groups of friends being injured or killed together which was demoralising for those left at home.

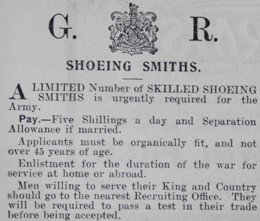

At the start of the war, horses were a very important means of transport, so people with skills associated with horses were in demand.

Blacksmiths and saddlers such as William Dickie of Catherine Street.

Privates James Grieve & Robert Henry both served with the Royal Army Veterinary Corps.

|

|

|

|

|

|

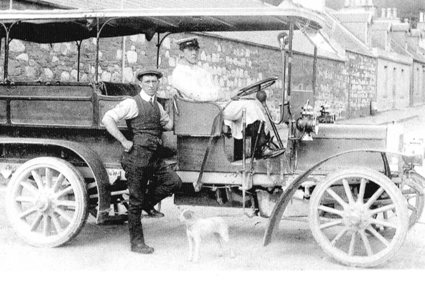

Private James Trainer was a blacksmith by trade. He re-trained as a fitter for the Motor Transport section of the Army Service Corps.

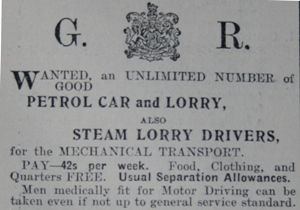

A knowledge of driving and of engines was important as the war progressed.

A knowledge of driving and of engines was important as the war progressed.

The Crosbie family - brothers George, Chris, James (Nick) and William ran a postbus and chauffeur business in Gatehouse with their father William. The brothers all became drivers with the ASC Motor Transport Division.

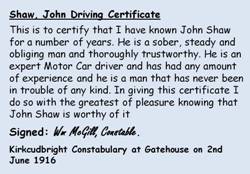

Knowledge of motor vehicles was one area where older men served abroad. Pte John Shaw was 36 when he enlisted in 1916. He was a shepherd but had taken driving lessons and served with the Royal Armoured Corps in France.

John Shaw sought a character witness.

|

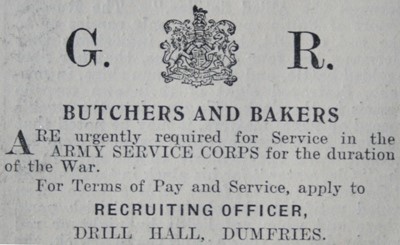

And don’t forget that healthy soldiers need to be well nourished.

|

The use of chemical weapons such as Chlorine Gas and Mustard Gas was a new development during the First World War.

Private George Orr from Belvedere Lodge was a chemist who first served with the Royal Army Medical Corps but transferred to the Royal Engineers Anti-Gas Establishment Unit where such things as gas masks were developed.

|

Captain James Learmonth, son of the headmaster at Girthon School, was studying medicine at Glasgow University when war broke out. During the war he became an expert on gas warfare and instructed troops on how to deal with gas attacks. After the war he returned to his studies. He became a famous surgeon and was knighted in 1949 after operating on King George VI. |

|

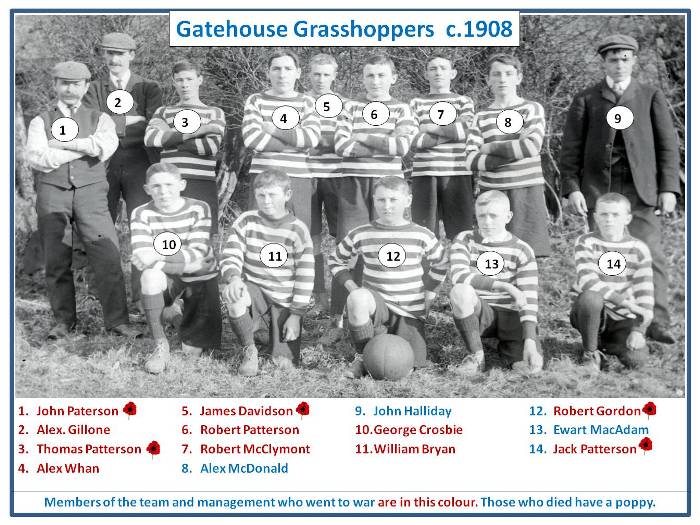

Private Robert Gordon of the Machine Gun Corps died of gas poisoning in July 1917. He had only been in France for 3 weeks and left a widow, Margaret and a young son. Before the war he was a keen footballer, a member of the Gatehouse Grasshoppers and was given the nickname Bobby Roy.

|

This was a Gatehouse youth football team. The description at the bottom of the photo says all that is necessary. It is likely that the team was disbanded during the War and probably never re-formed using the same name afterwards. Among the tributes offered at the official unveiling of the War Memorial in 1921, was a wreath was laid by The Gatehouse Comrades Football Team. Presumably this was a name used for a period after the War as a tribute to those who fought and particularly to those who died.

A number of members of the landowning families in the area joined the armed forces for World War 1. Some were already career soldiers but others left respected careers such as the legal profession in order to serve their country. Many had already served in the Boer War and / or in India.

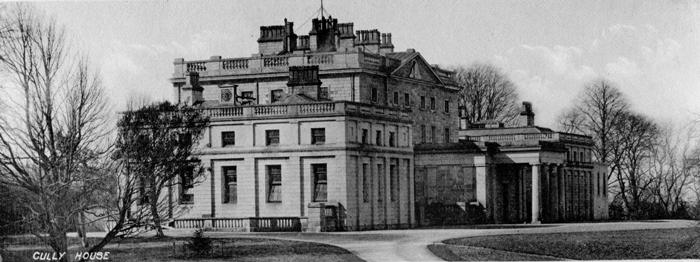

Cally Estate

On 8th August 1914, Colonel Frederick Murray-Baillie of Cally left Gatehouse to join the Cavalry Reserve. Prior to the war he had been a career soldier serving with the Royal Westmoreland Militia, rising to the rank of Major. Although he was in his fifties, he served in a vital co-ordinating role as a Railway Transport Officer in France during the Great War.

|

|

William Hewitt was the factor on the Cally Estate for about 17 years. He was related by marriage to the former laird of Cally, Horatio Murray Stewart. Both of William's sons, James and William Hewitt were born in Gatehouse and both were killed in the first months of the war in 1914.

|

|

Cardoness Estate

Lieutenant William F J Maxwell of the 5th KOSB was killed in Gallipoli in August 1915. He was the only son of Sir William and Lady Maxwell of Cardoness.

Kirkdale Estate

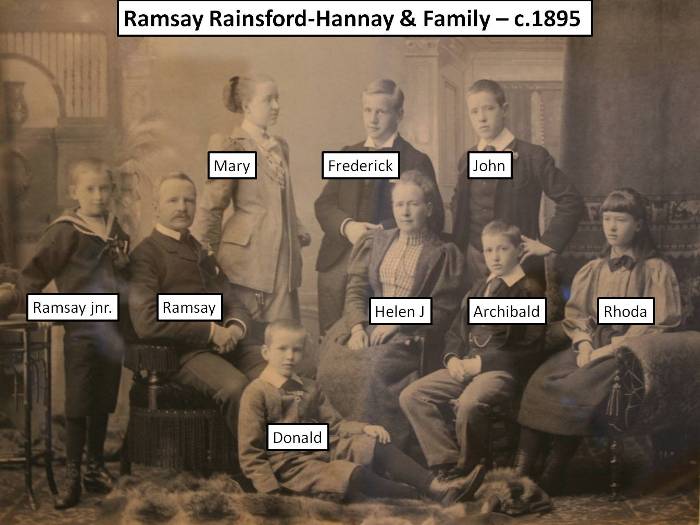

The Rainsford-Hannay family from Kirkdale had a strong military tradition. All 7 children of Ramsay and Helen Rainsford-Hannay were involved in the War Effort – the 5 sons became soldiers and the 2 daughters were nurses.

Major Archibald Rainsford-Hannay had previously fought in the Boer War. He was a prisoner of war in Germany in 1918. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Major Donald Rainsford-Hannay had attended Sandhurst and fought in the Boer War. He was badly wounded at Armentieres and later awarded the Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Lieutenant. Colonel Frederick Rainsford-Hannay had attended the Royal Military College, Woolwich and had fought in the Boar War. He served in France and Flanders for the duration of the war. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

Captain John Rainsford-Hannay was educated at Sandhurst. He was badly injured in 1917 at the Battle of Loos on the Western Front. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order.

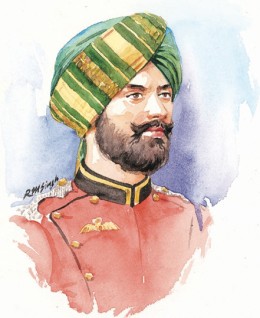

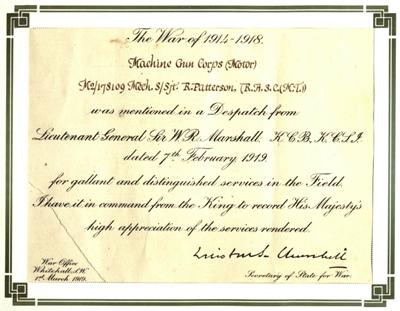

Captain Ramsay Rainsford-Hannay was educated at Sandhurst and had fought in campaigns in India. He was killed in Mesopotamia in February 1917 and posthumously 'mentioned in despatches' for 'gallant and distinguished conduct on the field'.

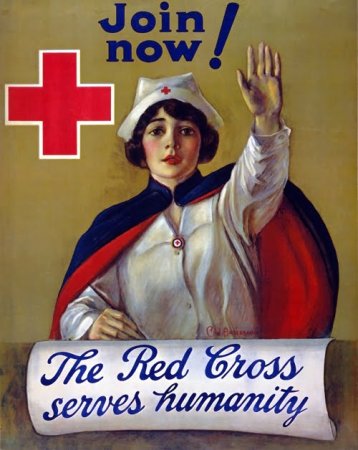

Mary Rainsford-Hannay, who later married Edward Cliff McCulloch was a Red Cross nurse.

Rhoda Rainsford-Hannay, sister of the above also served as a nurse.

Kirkclaugh Estate

|

|

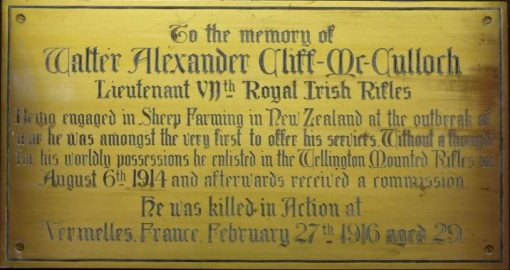

Lieutenant John G Cliff-McCulloch served in the Royal Navy. He fought in the Battle of Jutland, and was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for bravery. Lieutenant Walter Cliff-McCulloch was killed in February 1916 in France, fighting with the Royal Irish Rifles. |

Ardwall Estate

|

Three sons of Lord and Lady Ardwall were soldiers. Colonel Alexander McCulloch Jameson had fought in the Boer War and also in India. He served in Mesopotamia in the Great War. He later commanded the 5th Battalion of the K.O.S.B. Captain John Jameson was a lawyer who enlisted with the Imperial Yeomanry in the Boer War. He was a Major in the Great War and later an MP for Edinburgh. |

|

|

|

Brigadier General Sir Andrew Jameson McCulloch, the oldest of the brothers, adopted the surname McCulloch for inheritance reasons. Although he trained in law, he chose an army career, and rose through the ranks to retire as Commander of the 64th Infantry Brigade. He was awarded many honours. |

Father and Son

Robert A Mitchell was a law clerk in Gatehouse and also a member of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). He enlisted in 1916 aged 40 as a Lieutenant serving on minesweeping duties in the North Sea.

|

|

Robert and Agnes Mitchell had 5 children. Their oldest son Robert (known as Bob) enlisted in April 1917 in the RNVR. He first served on the HMY Medusa II . This was a luxury yacht converted for patrol duties. He later served as a telegraphist on HMS Merops also known as Q 28. Q boats were small freighters with guns concealed in a collapsible deck structure. They were used to lure U Boats (German submarines) to sail close to them, so that the Q boat crew could open fire at close range. |

|

Brothers in Arms

|

A number of families in the area sent at least 3 sons to fight. The McGarva familycame from Borgue, but during the war years they lived at Drawbridge Cottage Gatehouse.

Gunner Alexander McGarva : Royal Field Artillery

Alexander and Hugh were both killed during the war. |

|

The Patterson family.

John Patterson was a tailor from Birtwhistle Street. He and his first wife Elizabeth Hume had 5 sons, 4 of whom were soldiers :-

Private John William Patterson - killed at the Somme September 1916

Lance Corporal George Patterson - killed in action at Loos, France, Sept. 1915.

Private Robert Patterson King’s Own Scottish Borderers

Private Thomas B H Patterson - died in 1920 from wounds sustained in the war

After Elizabeth Patterson died in 1892, John re-married Mary Carson in 1896. They had 5 sons including 3 soldiers :-

Private David Patterson Royal Scots Fusiliers

Private Henry Patterson - killed in France April 1918

One other soldier brother

Transcript from Kirkcudbrightshire Advertiser, 18th October 1918

Private Tom Patterson, Royal Scottish Fusiliers, son of Mr John Patterson Birtwhistle Street, Gatehouse, has been wounded, and his leg amputated below the knee. Mr Patterson has had seven sons on active service. Two of these have been killed [George & Henry], one is missing [John William], and two are severely wounded [Tom & ??].

Robert Patterson, a joiner from Catherine Street was a brother of John Patterson the tailor. Robert was married to Violet Gordon. They had 7 children including 3 who were soldiers

Corporal John Patterson - killed at Arras March 1918

Staff-Sergeant Robert Patterson Army Service Corps

Private Henry Patterson Scottish Rifles

Margaret Patterson, sister of John and Robert Patterson, had a son :-

Gunner George Alfred Patterson (later Fisher) Royal Field Artillery - killed in France April 1916.

The McMurray family

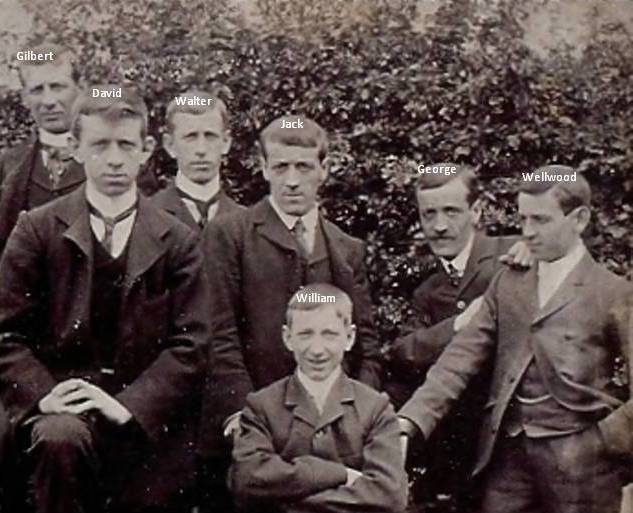

James McMurray and his wife Margaret Jane Anderson had twelve children, ten boys and two girls. Five of the brothers Adam, David, John, Walter and Wellwood became soldiers in the Great War. All survived and returned to play important roles in Gatehouse and the surrounding area.

|

Father James was a “letter carrier” and sons Adam, Walter and William also worked for the GPO, as did his grandson James McMurray. A number of the photographs used in this presentation were taken by William McMurray. Willie did not enlist, probably because he suffered from a curvature of the spine and would not have been accepted into the Forces. Ironically, as a rural postman who cycled everywhere, he was probably fitter than many young men who did enlist. At some point during the war, Willie went to London. It was there in the summer of 1918, that he married Jean Aird, a Wigtownshire lass, who was working as an ambulance driver. Willie and Jeanie returned to Gatehouse after the war to raise their family and for many years Willie was the Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths for Anwoth & Girthon. The McQuarries, the Shaws and the McSkimmings all had brothers and cousins who fought in the war. |

|

Soon after the British Government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914, the countries of the British Empire also declared war. Many of the men who enlisted had emigrated from the UK to find a better life. The general belief was that the war would be over by Christmas, and a free trip home with a chance to visit their families was an opportunity not to be missed.

|

|

CanadaThe Canadian Government mobilised troops in August 1914. Over 600,000 Canadians eventually joined up to fight, including over 20 from the Gatehouse area who had emigrated to Canada. The Canadian forces suffered a high casualty rate with over 67,000 being killed, including 12 of those from Gatehouse.

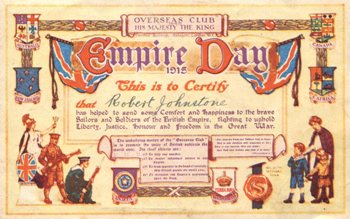

Lance-Corporal William Hope had emigrated to Ontario. He joined the 91st Canadian Expeditionary Force in October 1915. After the war he was presented with a Certificate of Service by the people of Thamesville thanking him for his contribution to the “Great European War”. His family in Gatehouse now have the framed certificate, reproduced here.

Private Adam Airley was born at Kirkcudbright and lived in Borgue. When his mother remarried the family lived at Skyreburn. He emigrated to Ontario and enlisted with 19th Battalion Canadian Infantry in 1914. Adam was killed on 3rd January 1915 at Ypres. Both of Adam's half brothers, Robert and Alexander Wilson, were also killed. Adam is remembered on the Kirkcudbright war memorial while Robert and Alexander are on the one at Borgue |

AustraliaAt least four local men are known to have emigrated to Australia and later joined the Australian Expeditionary Force.

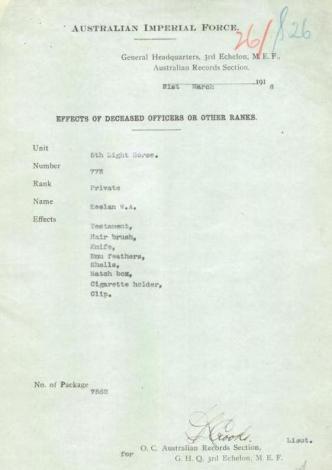

Trooper William Keelan was born in Gatehouse but latterly worked on farms in the Kirkcudbright area before emigrating to Queensland in 1907. He fought in the Dardanelles with the 5th Australian Light Horse where he was injured and sent to England to recover. He was allowed leave to visit his family in Kirkcudbright and whilst there met and married a local Dalbeattie girl Elizabeth McCoskry. |

|

|

Sergeant Daniel Pritchard was from Skyreburn School where his father John was the head teacher. He was a watchmaker by trade but he emigrated to Australia where he worked as a miner in the emerald and sapphire mines in Queensland. He joined the Machine Gun Corps and fought with distinction on the Western Front, winning a Distinguished Conduct Medal. Australian troops were easy to recognize by their distinctive 'slouch hat'.

|

|

|

|

New ZealandOver 5000 New Zealanders died in The War and are commemorated on the country's National Memorial at Wellington. Brothers Walter and John Cliff-McCulloch had emigrated to North Island New Zealand where they ran a sheep farm.

Trooper Walter Cliff-McCulloch enlisted with the New Zealand Forces on 6th August 1914. He was later commissioned as a lieutenant with the Royal Irish Rifles. He was killed in action in February 1916 at Vermelles, France.

John Cliff-McCulloch had been in the Royal Navy prior to his emigration to New Zealand. He rejoined the Royal Navy at the start of the war. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross from our Government and the Croix de Guerre from the French Government. After the war he returned to New Zealand. |

|

Sergeant William Potts from Barharrow Farm emigrated to South Island, New Zealand. He joined the Canterbury Mounted Rifles and served on the Eastern Front. |

|

|

|

IndiaCaptain Ramsay Rainsford-Hannay served with Rattray's Sikhs. He was killed in February 1917 in Mesopotamia. Captain William McMillan Black served with the 53rd Vaughan's Rifles (Indian Army). He was killed in October 1914. 2nd Lieutenant Donald Rainsford-Hannay served with the 53rd Sikhs Frontier Force. He rose to the rank of major and was awarded the Order of the British Empire (Military Division). |

AfricaSergeant Andrew Hogg, originally with the Gordon Highlanders, transferred to the King's African Rifles. He was involved in fighting in German East Africa (Rwanda, Burundi & Tanzania). He was killed in November 1917 and buried in Iringa Cemetery, Tanzania. Captain John Laurie was born in Gatehouse but had made his home in Africa. He served with the South African Scottish Horse in East Africa before transferring to The East Kent Regiment. He was killed at the Battle of Amiens in August 1918. Captain Robert S. Rattray served with the Gold Coast Regiment. He is reputed to have been involved in one of the first battles of the war in Togoland near the capital Lome. Togoland was a German Protectorate in West Africa. It is now Togo and part of the Volta region of Ghana. |

|

|

|

USA

The United States of America entered World War 1 in April 1917. Japanese HelpIn May 1917, the SS Transylvania was sailing through the Gulf of Genoa, carrying nearly 3,000 troops and nurses to Alexandria in Egypt. Although the ship was escorted by two Japanese destroyers, the ship was hit by a torpedo from a German U-boat and it sank within 40 minutes. On board was Corporal Jack Tait of the Desert Mounted Corps. Like many on the ship, Jack was rescued by the Japanese destroyer Matsu. Over 400 people drowned and many are buried in a special cemetery at Savona, Italy. |

Royal NavyRobert A Mitchell was a keen sailor and joined the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserves (R.N.V.R.), as did his son Robert (Bob) Mitchell.

It was possible to join the navy from age 14 as opposed to 17 for the army. James Ronald Faed joined the navy aged 14. Ronnie, as he was known by his family, planned a naval career. He attended Naval College and, as part of his training, became a Midshipman on the battleship HMS Goliath in 1913. On May 13th 1915 his ship was torpedoed in the Mediterranean Sea near the Dardanelles. Of the 700 crew members, 570 were drowned, including Ronnie. The most senior local seaman was Lieutenant John G Cliff McCulloch who rejoined the Royal Navy at the outbreak of war. He took part in the Battle of Jutland aboard HMS Malaya and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry.

|

|

|

|

Royal Flying CorpsThe RFC was officially formed in 1912. Early in the war its main duties were photographic reconnaissance and helping to direct artillery fire. As wireless communication and better aircraft became available, the RFC took on bombing raids on industrial sites and important transport links. This led to aerial battles with German fighter planes (dogfights). Flying was still in its infancy and the German's had more sophisticated planes and better trained pilots. As a result the loss of life was very high - about 1 in 4 were killed - which was equivalent to trench warfare.  |

Early RFC recruits seem to have come from other existing military units. Arthur Rullion Rattray had been serving as a Lieutenant in the Indian Navy. He transferred to the RFC and was involved in several “enemy hits”.

Royal Air Force

In May 1918 the Royal Flying Corps, then part of the British Army, merged with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to form the Royal Air Force (RAF).

James C McMichael was a sergeant with the Highland Light Infantry before transferring to the RAF.

Joseph Carson from Conchieton was an Air Mechanic 1st class with the RAF.

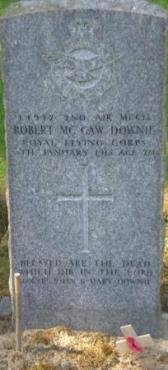

Robert McG Downie was killed on 8th January 1918. He was an Air Mechanic 2nd class.

He lived in Gatehouse when he was young although his parents later moved to Inverkeithing, Fife.

On the Gatehouse War Memorial he is listed as R McG Downie RAF.

On the Dalgety Bay War Memorial in Fife he is listed as Master Mech. Robert M. Downie RFC.

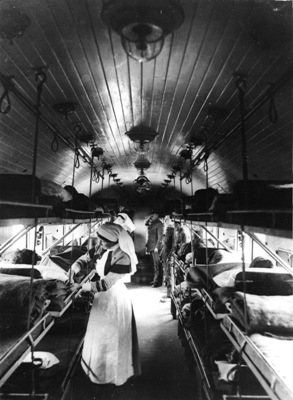

Dealing with dead and wounded soldiers was a well organised operation.

Wounded were carried from the battlefield on stretchers by the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) for basic treatment at a First Aid Post. They would then be taken several miles by ambulance, often over rough ground, to a Dressing Station, which was often housed in tents.

Private James Sinclair (known to his friends as Bosie) served in Egypt and Gallipoli with the Royal Army Medical Corps.

Private William Caig, formerly a shepherd at Grobdale, sent a letter to the local Minister of Girthon, Rev John Stewart, describing his work with the field ambulance in France.

'My present job is a stretcher-bearer. It is heavy work and sometimes risky, but one is repaid for it all by the gratitude of the brave fellows.'

Many men recovered sufficiently from their injuries and returned to the Front to fight. Those who had recovered sufficiently from shell shock were given duties at home rather than be returned to the Front Line.

|

The seriously wounded were moved to Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) which were usually close to railway lines or canals to ease the transport of patients. Every division had a least one Stationary Hospital (SH) which could hold up to 400 wounded patients.

The badly wounded would be sent to a General Hospital (GH) to recover, which was often a hotel or large house which had been requisitioned. If a patient did not die or recover quickly, he would be sent back to Britain to a military hospital to complete his recovery. This would involve being transported home by Hospital Ship. |

|

|

Large houses such as Drumlanrig Castle, Dumfriesshire were requisitioned as Auxiliary hospitals for men to convalesce but smaller local hospitals such as the one in Castle Douglas were also used.

Conditions for the nurses were difficult and very soon their ankle length skirts were shortened and they had to be issued with gumboots to cope with the mud. They had to cope with rat infested mattresses and lice in their billets, which spread disease. Many nurses caught infections. The Spanish flu epidemic of 1918 killed many nurses. |

|

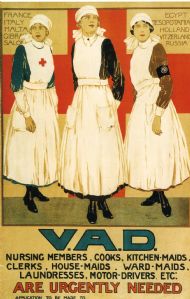

Nursing organisations were overwhelmed by the huge number of casualties. Although many nurses were well trained , many were taken on as new recruits. Many middle class and upper class girls volunteered such as Mary Cliff-McCulloch who was a Red Cross nurse who worked in Boulogne, France and in home hospitals. Her sister Rhoda Rainsford-Hannay joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses in Plymouth.

|

|

Older nurses came out of retirement to fill the vacancies at home left by those who had gone to the Front. A number of local women joined various nursing organisations. |

|

|

Bessie Thomson from Creetown was a VAD Nurse at St Omer in France. She was killed in September 1917 when the 58th Scottish General Hospital was bombed.

She is mentioned on the Kirkmabreck War Memorial, Creetown, one of the few women to be remembered on a World War 1 memorial. |

Doctors were in short supply during the war and an increasing number were women. Dr Flora Murray from Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire was a medical pioneer who ran hospitals in France, as part of the Woman's Hospital Corps, and also in London.

|

Jean Aird, later wife of photographer William McMurray, was in London during the war and was an ambulance driver.

The Woman's Reserve Ambulance (Green Cross Corps) was attached to the Metropolitan Police. They handled patient transport between hospitals but also dealt with emergencies such as the Zepplin bomb attacks. |

Women also drove ambulances in France and other battle areas, going close to the Front Line to collect victims. These were usually organised by the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY).

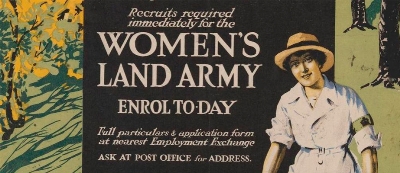

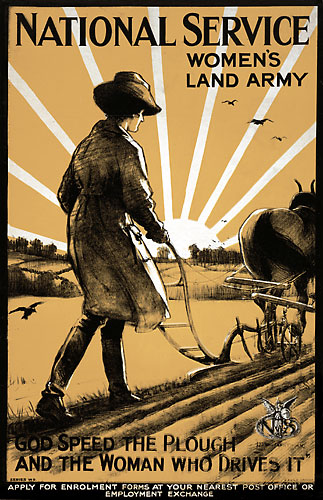

In the 1911 census, Anwoth and Girthon had a population of less than 400 young men between the ages of 19 and 40. Over 100 men from the immediate area enlisted for war, so there was a shortage of manpower to do much of the work around the town and women had to take up many of these jobs.

|

Family businesses often struggled for workers. William Crosbie ran a post bus and garage in Gatehouse. In April 1917, William asked the army to send his son George Crosbie home. The appeal was turned down as the army said that a younger brother (Nick, who could not drive!) could be used as a worker instead of George. Later, in 1918, Nick also joined the army.

Food Supply |

|

Farming

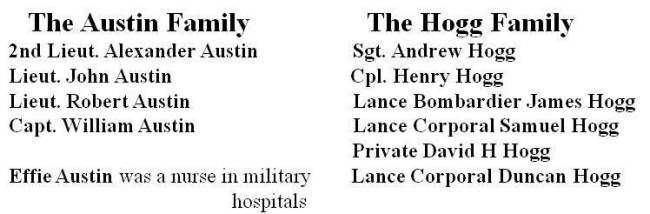

The Austin and Hogg families were farmers, and like many agricultural workers they moved frequently to different farms around the Gatehouse area. They were typical of many young farmers who joined the Forces.

|

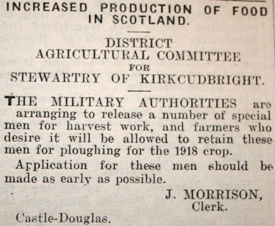

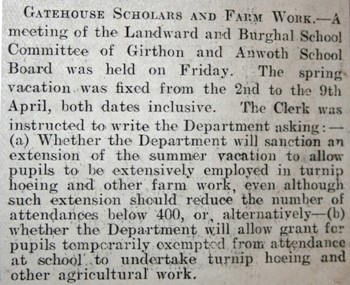

Conscientious Objectors, who had refused to fight, would also help on farms. Some men were released from army duty at harvest time and allowed to return home to help out.

Children also helped with food supply by collecting berries and rose hips (which provided vitamins) and helping with tasks such as harvesting potatoes and turnips.

Factory Work

Morale Boosters

Fund raising events were held help the war effort. Even children were encouraged to save. |

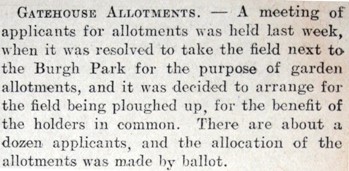

The Gatehouse Horticultural Society cancelled the Flower Show in 1914. The next show did not take place until after the war ended. The society organised the hiring of a potato spraying machine in 1917 to encourage potato growing in gardens and in the new allotments at Burgh Park.

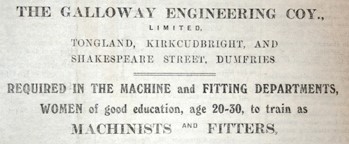

Women were encouraged to help with factory work. There were no factories in Gatehouse but The Galloway Engineering Company at Tongland near Kirkcudbright, which had made Arroll Johnstone cars, was producing parts for aircraft.

A factory at Heathhall near Dumfries made wings for Sopwith Camel aeroplanes.

|

|

With so many of the young farmers away at war, many women had to work on farms to grow as much food at home as possible. Farming was hard work - it was less mechanised than today and horses were in short supply as many had been sent away on war duty.

|

|

Refugees

When Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, many Belgians decided to flee their country and about 250,000 of them came to Britain, with about 8,000 coming to Scotland. Glasgow was the main distribution centre in Scotland and much of the work seems to have been organised by the Roman Catholic Church.

Alexander and Marie Van Uytrecht came to live in Gatehouse in 1914 with their four children - Francois (11), Roza (7), Leopold (6) and Paula (3). Leopold was an invalid and unable to walk. Alexander had been an engine driver in Belgium before the war.

The Van Uytrecht family lived in Gatehouse until 1917. The children attended Girthon School and Francois became good enough at English to win an essay-writing prize in 1917.

Other Belgian families settled in Creetown - in houses provided by Mr Rainsford-Hannay of Kirkdale .

Newspapers

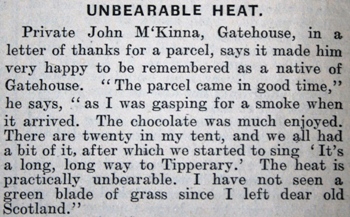

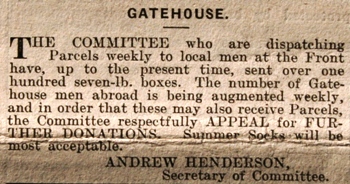

As well as informing the community about injuries and deaths, local newspapers also printed extracts from letters written home and helped to co-ordinate Parcels for Soldiers.

Letters Home

Men were actively encouraged to write home. Sometimes this was to alleviate boredom on long sea voyages through the Mediterranean Sea to the battlefields of the Eastern Front. The men saw many new and interesting sights which they described in their letters. They also described the fear of torpedoes and how they coped with it.

Letters were checked by a senior officer to ensure that no information that would be helpful to the enemy was sent.

|

Between August and December 1914, about 100 men left Gatehouse to fight to go to war. People were shocked by the first war deaths reported in October 1914, including :-

There are many sad and heartbreaking stories connected with the war but probably the story most remembered in Gatehouse is that of the Davidson family.

Private James Davidson of Gordon Highlanders was killed in France on 4th January 1917 (aged 25) |

|

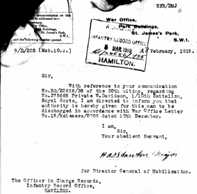

The first news that a family received of the death of a loved one was usually by formal letter from Army Headquarters, although a telegram might be sent for the death of a senior officer.

This would be followed by a more informal letter, usually from the soldiers’ commanding officer explaining the circumstances of his death.

The Honourable William and Mrs Evelyn Hewitt, parents of 2nd Lieutenant William Hewitt, received several communications from the army :-

• 13/10/1914 - telegram saying that William was missing

• 16/10/1914 - telegram saying that he was wounded

• 18/10/1914 - telegram saying that he had been 'found dead'

• 26/10/1914 - telegram saying he was 'killed in action'

Some time later, they received a letter explaining the circumstances of William's death and that he was buried in a small grave near Croix Barbee.

His body was later exhumed and re-buried in the Vielle-Chapelle Military Cemetery at Lacouture.

|

Missing in Action |

|

The huge number of casualties in World War 1 meant that many of the dead were never identified and were buried in unknown graves.

These unknown soldiers are commemorated in war cemeteries found around the old battlefields and on memorials such as the Thiepval Memorial, shown here,

• On the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916 over 19,000 men were killed.

• The Thiepval Memorial commemorates 72,000 dead from the UK and South Africa.

• 90% of these were killed between July and November 1916.

• There are 300 British headstones and 300 French grey stone crosses.

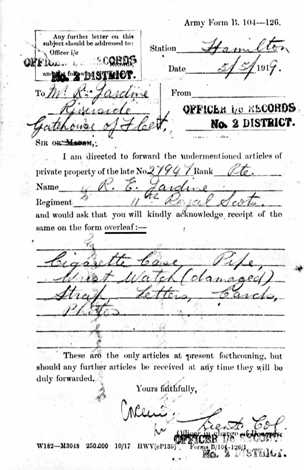

The personal belongings of a dead soldier had to be returned to his next of kin. There were occasions when the family disputed whether all of a soldier’s belongings had been returned.

|

|

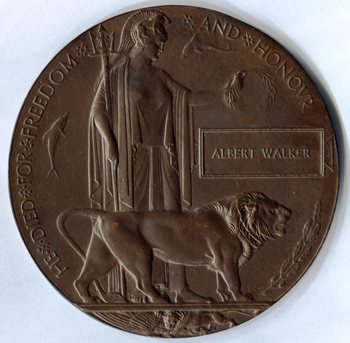

After the War was over, the family of each soldier who was killed in the War was sent a personalised Memorial Plaque which was made of bronze and was about 5 inches in diameter. Partly because of the design, this plaque was often referred to as the Dead Man’s Penny or the Widow’s Penny. It was inscribed with the soldier’s name but no rank, intending to show that there was no distinction in sacrifice between the ranks. Each plaque was accompanied by a scroll from the King and a letter reflecting the fact that the award had been made.

Acting Sergeant Albert Walker, K.O.S.B. was killed in Palestine on 13th November 1917 aged 21.

|

The peace agreement was signed at 5am on 11th November 1918. All hostilities were ordered to cease by 11am that morning. Fighting continued right up until 11am. Thousands of men were killed on the last day of the war.

In Gatehouse the event was marked by an announcement by Provost Campbell at the Town Clock and the raising of a flag on the tower. Rev. John Stewart held a Thanksgiving service in Girthon Parish Church. Later in the day a bonfire was lit on Gatehouse Hill and a dance held in the Town Hall.

|

|

The end of the War had been anticipated for some time and a Homecoming Fund had been set up to welcome the soldiers home.

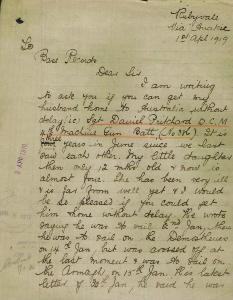

This letter was written in April 1919 by Sergeant David Pritchard's wife in Australia who hadn't seen her husband for 3 years and who had a sick 4 year old daughter. |

Memorials to those who died were erected in most parishes. Many churches and public buildings had their own commemoration to locals who died.

In France and Belgium are several memorials at sites of mass burials. The British National War Memorial was opened as The National Arboretum at Alrewas, Staffordshire in 2001.

Civic War memorials

Most parish War Memorials were erected in the early 1920's and are named after the parish in which they are located :

• Anwoth & Girthon War Memorial is in Gatehouse of Fleet

• Tongland War Memorial is in Ringford

• Kirkmabreck War Memorial is in Creetown

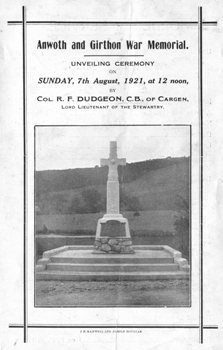

The Anwoth & Girthon War memorial is based on the Dupplin Cross - an ancient Celtic cross found in Perthshire, and it was suggested by the Kirkcudbright artist E A Hornel. He also suggested designs for several other memorials in the region. The cross has carvings of many symbols which are explained on a board beside the memorial.

The unveiling of the war memorial took place on a damp Sunday afternoon in August 1921. A united service was held in Girthon Parish Church. A procession, led by pipers Robert Veitch and George Maxwell, which included over 50 ex servicemen and local dignitaries, marched to the new War Memorial. The Lord Lieutenant of the Stewartry, Col. R F Dudgeon, performed the unveiling. The last post was sounded by Lieutenant Livingstone.

|

|

Wreaths were laid by officials including the Town Council and the Freemasons, as well as many of the families who had lost loved ones. Local groups and societies also remembered fallen colleagues. The Gatehouse Comrades football team, laid a wreath “In loving memory of our fallen comrades”.

Church Memorials

Borgue Free Church Roll of Honour is now in Borgue Village Hall.

Some church memorials have been removed all together. Tarff Free Church at Ringford is now a private home. The memorial stained glass window has been removed and is damaged. |

Town & Village memorials

As well as the parish memorials some towns and villages erected their own memorials and Rolls of Honour.

New Galloway has a hand painted Roll of Honour, said to be the work of local artist Jessie M. King, while St John's Town of Dalry has a very grand wooden Roll of Honour in the Village Hall.

|

Clubs & Societies Memorials can be hidden away in unlikely places. Castle Douglas Carpet Bowling Club has a lovely hand painted memorial.School Memorials

Some schools have Memorials or Rolls of Honour which sometimes name those who survived as well as those who died. University Memorials

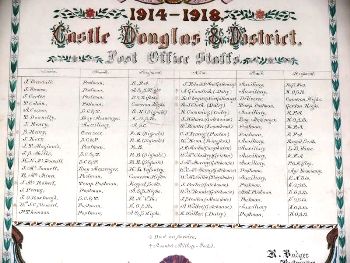

Edinburgh University (Lieutenant J B McGlashan) Work-Related Memorials St Giles Cathedral - the memorial to Church of Scotland Ministers names Rev F W Saunders of Anwoth Church. He served as a fighting soldier not as a minister. Castle Douglas Post Office - a Roll of Honour naming local postal workers including Private James McMurray (killed October 1916) and Private Adam McMurray (who survived) |

|

|

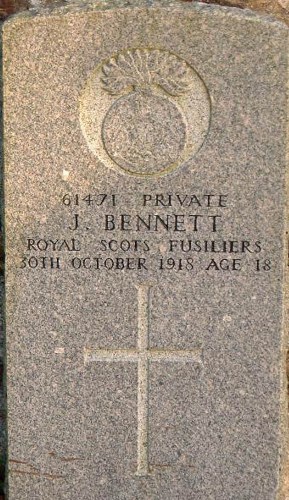

Graves

Special war graves are of a distinctive style showing a company badge, name, rank and number of the soldier commemorated. The huge war cemeteries in France, Flanders and Galliopli contain hundreds of these graves which are maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) but there are also examples in local graveyards.

|

|

|

The Stewartry Roll of Honour

The editor of the Kirkcudbright Advertiser intended to publish a book after the war with details and photos of local soldiers, sailors and others involved in the war. The book was eventually published in 1927 but was a reduced version with no photographs and relied on family members supplying many of the details, so many people have been missed out or there are few details about them. |

|

|

1914 Star or 1914-15 Star"Pip"

|

British War Medal"Squeak"

|

Victory Medal"Wilfred"

|

This particular set of 3 medals was awarded to Albert Walker.

|

The medals, as a set of three, were nicknamed Pip, Squeak and Wilfred after a cartoon published in the Daily Mirror. Pip was a dog, Squeak a penguin and Wilfred a rabbit. Some people only qualified for the last two medals - usually if they enlisted after 1915. These two medals, as a pair, were nicknamed Mutt & Jeff, also popular cartoon characters.

|

|

|

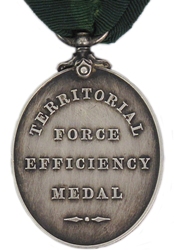

Awards for gallantry by Officers :- · Distinguished Service Order · Military Cross. The Distinguished Service Cross was the naval equivalent of the MC. The Distinguished Flying Cross was awarded for gallantry in the air. |

D.S.O. |

D.S.C |

D.F.C. |

Brigadier General Andrew J McCulloch was awarded the DSO.

Lieutenant John Cliff-McCulloch of the Royal Navy was awarded the DSC.

Brigadier General McCulloch was also awarded the Croix de Chevalier and the Legion of Honour.

Those below officer rank could be awarded :-

• Distinguished Conduct Medal

• Military Medal (after 1916)

• Mentioned in Despatches

Nurses had their own awards.

Mary Cliff-McCulloch was awarded the Order of the Red Triangle for her Red Cross work, while Nursing Sister Helen Caig of Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service was awarded the Royal Red Cross.

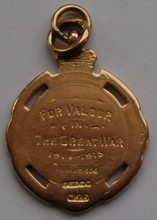

After the war, a committee representing the Town Council of Gatehouse and the Parish Councils of Anwoth & Girthon, awarded gold medals to local soldiers who had won war decorations for conspicuous gallantry.

These medals were to be awarded at the unveiling of the war memorial in 1921. The men receiving them had already been awarded the Military Medal.

|

|

Receivers of the Gatehouse & District Gallantry Award Andrew Straiton Rev Alexander S Campbell David Veitch Henry A McClellan James McGarva William McGarva |

|

Horses

The 1914 Gatehouse Foal Show was attended by officers buying horses for the Kirkcudbright Battery of the Royal Field Artillery. Farms and estates all over the country were forced to sell their horses and mules. The army paid up to £75 for a large charger.

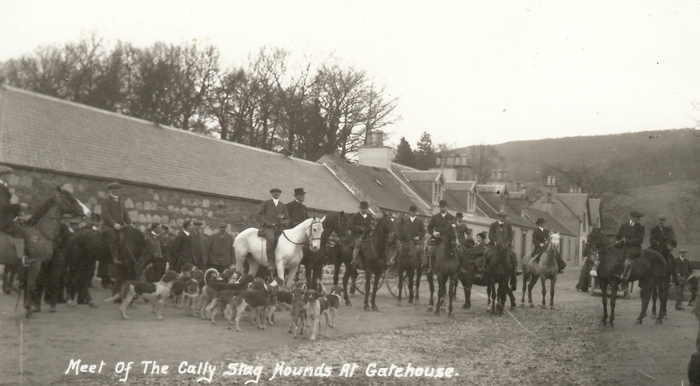

Many horses in this picture of a Cally Hunt just prior to the war would have been sent to the Front Line.

The man on the large gray was Albert Douce the huntsman. He had come to Gatehouse from Leicestershire with the hounds for the Cally Stag Hunts and later married local girl Elizabeth Thomson from Cairn farm. At the outbreak of war he joined the Cameron Highlanders.

Over 700,000 horses and mules were used by the British Army during the war. There were not enough horses available in Great Britain and many were shipped to Europe from North America.

About 15% of horses were lost each year. Horses suffered greatly. Many were killed by gun fire and poison gas but the biggest killers were hunger and illness. The horses and mules needed huge amounts of hay and oats which were difficult to supply and although the army had teams of vets many died from disease.

Private James Grieve served with the Royal Army Veterinary Corps on the Western Front.

Private Robert Henry served at the Veterinary Hospital in Winchester.

In previous conflicts, horses were used for cavalry charges but the new war techniques of trench warfare and use of machine guns made this use of horses less important.

Instead they were used for transport - pulling ambulances, artillery and supplies and were often more reliable over the rough muddy ground than motorized vehicles. They were useful for reconnaissance work and carrying messages.

Soldiers liked horses and they boosted morale but unfortunately they also increased pollution around the trenches.

After the war ended there was a huge problem dealing with the thousands of horses, most in bad health. Quarantine restrictions prevented most from being returned home. Of the 136,000 Australian horses (called walers) involved in the war in Gallipoli, only one, named Sandy, returned to Australia.

Sandy was the mount of Major General Sir William Bridges, who was killed in May 1915 in Gallipoli. Sandy was taken first to Egypt to recover and then back to Britain. The horse was eventually shipped back to Australia in 1918, thus fulfilling Major General Bridge's dying wish. Sandy died in 1923.

Dogs

Dogs were used for many purposes. A Dog Training School was opened in Hampshire in 1917.

Casualty Dogs - carried first aid to the wounded in the battlefield.

Guard Dogs - acted as sentries warning of enemy approaching without barking.

Scout Dogs - smelt out the enemy and signalled their presence by bristling their hair and pointing their tails.

Messenger Dogs - were less likely than soldiers to be shot by snipers as they carried messages from the Front Line to headquarters.

Smaller dogs such as terriers were often kept as pets in the trenches and were excellent rat catchers.

Private James Sinclair (known as Bosie) served with the Royal Army Medical Corps in Egypt and Gallipoli. He sent home pictures of his small pet dog doing tricks.

Pigeons

Radio Communications were still very rudimentary during World War 1. Pigeons were a popular and reliable way of sending messages from the Front Line to headquarters. The pigeons could find their way back to their lofts even if they had been moved.

|

|

MascotsMascots are an important part of army life, providing a distraction and pleasure for the troops.

Cats were important as they also good at catching rats and mice in the trenches. The 1st Scottish Rifles (the Cameronians) found a new born donkey during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The soldiers named the foal Jimmy, and fed him on tinned condensed milk and other rations. Jimmy was promoted to Sergeant and remained with the troops on the Front Line, working for his keep and although he was wounded three times, he survived. After the war he was taken to the soldier's home base at Peterborough. He became a local celebrity raising money for the RSPCA. He died in1943 and has a memorial in Peterborough. Some troops had more bizarre mascots including a coyote and a monkey. The Canadians had a brown bear called Winnipeg. They brought him to England with their troops but Winnipeg was left at London Zoo during the war. He is said to be the inspiration for AA Milne to write his Winnie the Pooh stories.

|

Remembering Them |

|

The red poppy is the flower that is recognised worldwide as a symbol of remembrance of those who have died in conflicts.

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Scarce heard amid the guns below

Take up our quarrel with the foe: |

A Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, was working in a hospital near Ypres. When a close friend died, he wrote the poem 'In Flanders Fields'. John McCrae's family were from Scotland, his grandparents having emigrated from Ayrshire to Guelph, Ontario in 1849.

In November 1918, an American, Mrs Moina Michael, read John McCrae's poem and of his death in January that year. She was so moved that she swore to wear a Red Poppy to remember the servicemen who had been killed in the Great War. She campaigned for it to be accepted as an international symbol of remembrance. |

|

Even after 4 months of war, there was a feeling amongst the troops that it would soon be over. |

|

In late 1914, a 'Sailors & Soldiers Christmas Fund' was created by Princess Mary, the seventeen year old daughter of King George V and Queen Mary. The purpose was to provide all servicemen on duty overseas on Christmas Day 1914 with a 'gift from the nation'.

It was decided to spend the money on an embossed brass box which was filled with some combination of cigarettes, pipe, lighter, tobacco, bullet pencil, sweets, spices and chocolate. The package was accompanied by a greeting card.

It has been estimated that 65 million men took part in The Great War. Of these, 10 million were killed and a further 20 million were wounded. The scale of devastation was much greater than in any previous war, partly due to mechanisation, the ability to manufacture and use weapons and armoury at an alarming rate, but also because of the use of deadly gases.

The sheer amount of human involvement and death led people to think in terms of it being “a war to end all wars”, and it would be nice to think that we might all have learned our lesson, and that we cannot again allow a small number of powerful, influential individuals, who were misguided if not insane, to initiate such carnage. We have since experienced the Second World War, and conflicts throughout the world continue today, so the “war to end all wars” clearly didn’t live up to its billing and the lesson of diplomacy still has to be learned by too many of us.

Private William Macaulay

Private William Macaulay

.jpg)

.jpg)