|

Life in Gatehouse

|

|

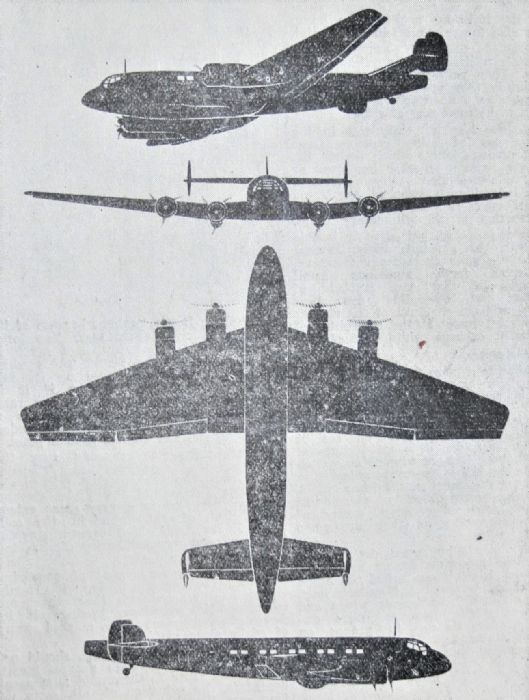

Fortunately Gatehouse was not subjected to air raids, but many enemy planes did pass over South-West Scotland. In 1940 several bombs were dropped into fields nearby, probably in an attempt to lose weight before returning to Germany after raids on Glasgow. Propaganda leaflets were also dropped. Juliano Frullani remembers hearing the muffled drones of low flying aircraft at night and thinking that ''they seemed to scrape their bellies on our chimney tops''. The picture (right) is the 3rd of 4 cards which shows various viewpoints of a Junkers JU 90 which has a wingspan of 115 ft and length of 86 ft., four engines, low wing, two rudders, tapered wings, square-cut wingtips and tailplane. In Castle Douglas there was a Royal Observer Corps who were trained to spot enemy aircraft. |

|

There was a very real fear that the Germans would drop poisonous gas bombs. Every British citizen was issued with a gas mask, to be carried at all times.

|

|

Leo McClymont remembers taking his mask to school each day. If anyone forgot their mask, they were sent back home to get it. The masks were horrible to wear and had a nasty smell but children enjoyed making rude noises through the tubing. The school held regular fire and bomb attack drills. Leo remembers being taking up the road towards Gatehouse Station and having to dive behind hedges or into ditches when 'an attack' happened. |

|

|

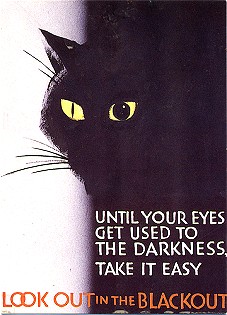

As early as July 1939 the Government were warning of a need to prepare for a blackout as they feared an air attack by Germany. The blackout came into force on 1st September 1939, before war was declared. |

|

|

The blackout involved covering all windows and doors with thick material or cardboard to block ANY light escaping. It was enforced by the ARP (Air Raid Precaution) officer and heavy fines were inflicted on those who did not comply. Street lights were switched off or dimmed, and car headlights had special covers. Commander Cochrane from Rusko House was a local ARP officer. |

|

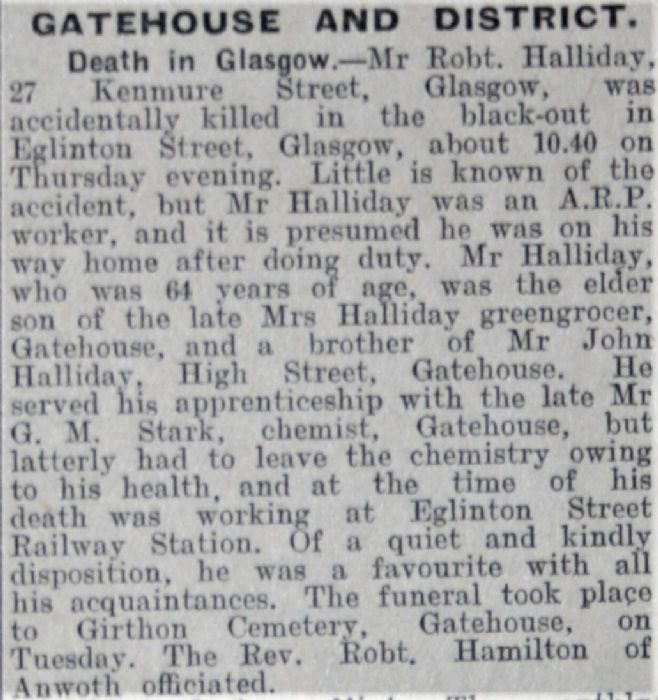

Many people were killed or injured in road traffic accidents or by bumping into or falling over objects such as into docks or rivers. Robert Halliday of Gatehouse was killed in 1940 in one such accident. |

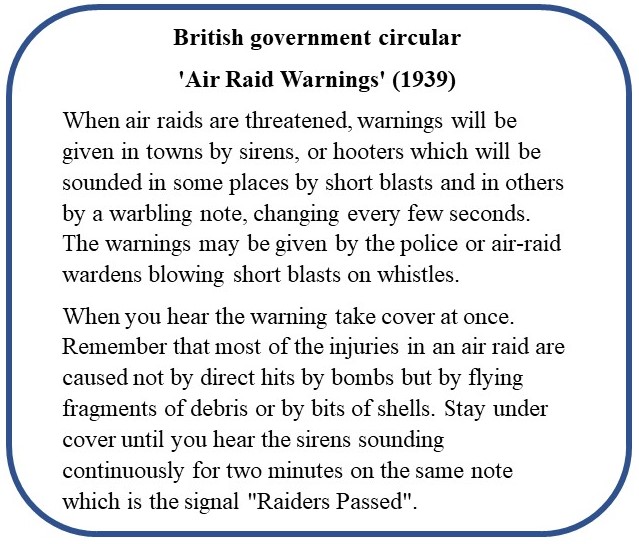

A system was put in place to warn people of imminent bombing attacks.

Fortunately, in Gatehouse, it was never used in earnest, but the siren was tested every week in Gatehouse until at least the 1950s |

Incendiary bombs and fire were a real concern and there was much discussion at the Town Council about the response to a large fire. Eventually a new fire tender was supplied and housed in a building in Victoria Street.

The firemen in Gatehouse were (and still are) volunteers.

Sir Philip Macdonell, a retired judge who lived at Woodlyn, Dromore Road was the local convener with regard to Fire Brigade matters. He represented the Gatehouse Town Council at various conferences and committees around Galloway.

There were also appeals to householders to clear their attics of rubbish to decrease the fire risk.

|

|

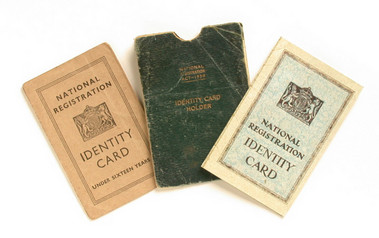

Everyone had to be issued with an ID card, primarily to control the use of ration books. At the beginning of the war all ID cards were brown, but in 1943 adults were issued with blue ones. These were very important documents– no ID card meant no food and clothing rations. They were issued together with a holder to protect them. Each person had to register at a shop of choice and the ration books were stamped as they were used. |

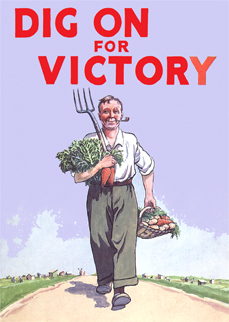

Food supply was a huge concern during the war, Britain was not self sufficient in food, and other goods.

The Ministry of Food was set up to control the regulation of food production and fair distribution.

Some groups such as the armed forces and land girls were allowed extra rations.

For example:

1940 saw the rationing of various foods such as butter, bacon, meat, sugar and tea.

1941 cheese and eggs added.

1942 tinned vegetables, rice, biscuits and sweets (2oz (55g) per person per week!).

1943 sausages.

Isolated places such as Gatehouse were much better off than the cities.

|

|

|

|

Rusko House resident Cecilia Cochrane commented: “In a lot of ways we hardly knew there was a war on. The garden produced excellent fresh fruit and vegetables. The river was filled with salmon and trout; the estate was home to all varieties of game. The farm provided us with fresh milk, butter, cream and eggs. My father cherished several hives of ...Italian bees”. from Little Bits by Cecilia Cochrane.

When fruit was being picked the WRI could arrange for extra sugar rations to make jam - a good way of preserving fruit. Children were encouraged to help - lifting new potatoes, and collecting brambles and rosehips.

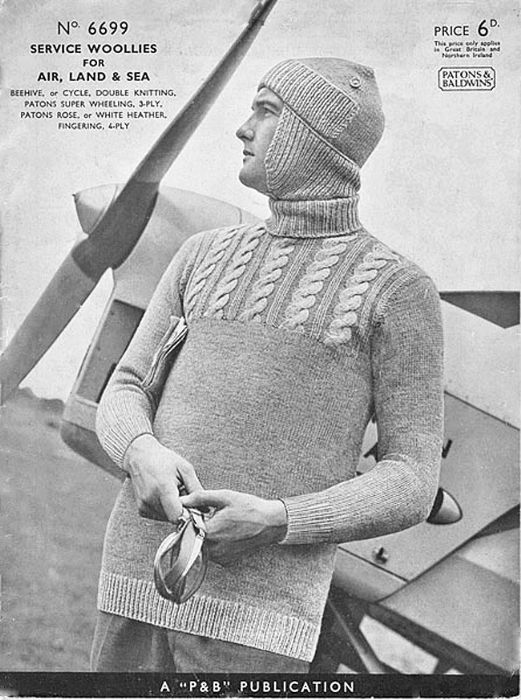

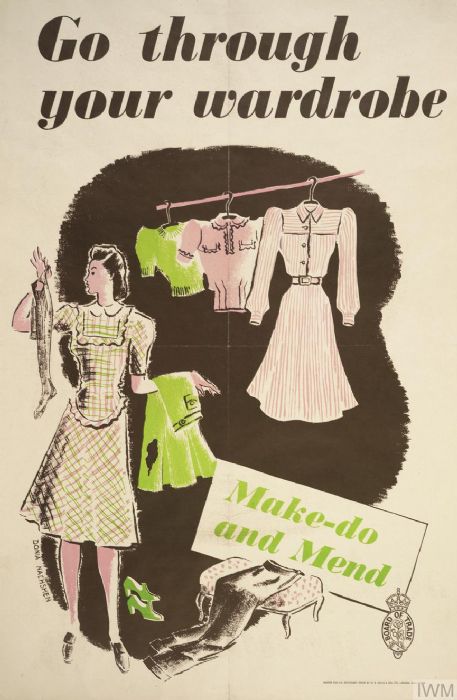

Many materials for clothing such as cotton and wool were imported. During the war years up to a quarter of the population were entitled to wear a uniform, the production of which, led to a great strain on the clothing industry.

Rationing was introduced to allow for fair distribution of the meagre resources.

Items of clothing were allotted points based on the amount of material and labour needed to produce it. So as well as paying for the cost of the item ‘points’ were deducted from a ration book.

e.g. a dress = 11 points; mens' trousers = 8 points

Mothers with babies and growing children had extra rations.

|

|

|

|

|

A 'make do and mend' campaign encouraged re using clothes. Exchange of unwanted clothing was encouraged and organised by the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service. Fashions changed and many women, like Margaret Sproat (right), cook at Cally House School, wore trousers for the first time. They were more practical for night time air raids and took fewer rationing points than a skirt. Siren suits were easy to put on when you needed to get to an air raid shelter quickly.

Dr Kennedy McCreath was G.P. in Gatehouse from 1969 to 1981. He did not train as a doctor until after the war. He served with the 1st Armoured Division of R.A.S.C. and was at the Dunkirk evacuation. He married Peggy on 24th September 1940 in Glasgow. The back of his wedding photos states: 'should have been married on 11th September, leave cancelled 10th September, - wedding off.' |

|

|

Weddings, of which there were many during the war years, were a problem for brides, many of whom were married in a suit or day dress. Others borrowed or were given extra coupons by friends to buy a new wedding dress. Others used a second hand dress. Some had innovative ideas such as using parachute silk for a dress. The groom was often in uniform.

|

|

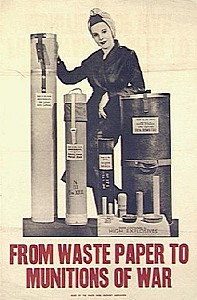

Salvage collection was another way to make the best use of available resources. Adverts were placed in the local newspapers for the collection of paper, metals and bones. Quantities collected in each town were published in the Galloway News. Gatehouse always seemed to do well. The Scouts helped with the paper collection which was stored in an old unoccupied house ready for collection - 43 Catherine Street. Books and magazines were also collected - later in the war some were used to replace destroyed library stocks and others sent out to the troops. Metal was also collected and some buildings had their railings removed. The Town Council considered donating metal parts from the old swing bridge over the canal beside Cardoness Castle. Metal was stored in a council building at 9 Digby Street (now flats).

|

Petrol was rationed from the beginning of war, so travel was difficult. Trains still arrived at Gatehouse Station and were met by a bus for transport into town.

Bicycles were a favourite form of transport for shorter distances. Bikes had to have lights in the blackout and there are numerous examples of people being fined for 'no rear lights' during the war years.

Jim Grieve remembers being stopped by the policeman for such an offence.

One night after a game of football at Cardoness with a pal, they were cycling back home when they passed the local policemen. The policeman called ‘OK boys where are your lights?’ The boys took fright, pulled their caps over their faces and sped away. The following day they were eating their ‘piece’ in Killiegowan Woods when the policeman arrived, chatted casually to them then said ‘By the way you will be hearing about appearing in court in Creetown for riding a bike without lights’.

In due course the letter arrived and Jim and his friend went off to Creetown, Jim with 10 shillings from his mother for the fine. As they arrived they met some other young men who had just been fined 25 shillings for the same offence. But it was Jim’s lucky day. A court official asked him his age. When he discovered that he was only 15, and hence only a juvenile, he was let off with a caution.

|

Fighting a war is an expensive business. People were encouraged to save. The Galloway News had many adverts for savings schemes. There were numerous whist drives, dances and bring-and-buy sales with proceeds going to various war charities like the Red Cross. Some ladies collected bunches of wild flowers such as snowdrops, primroses and violets to be sold in the cities to raise funds. In Gatehouse this was organised by Norah Henderson.

|

|

|

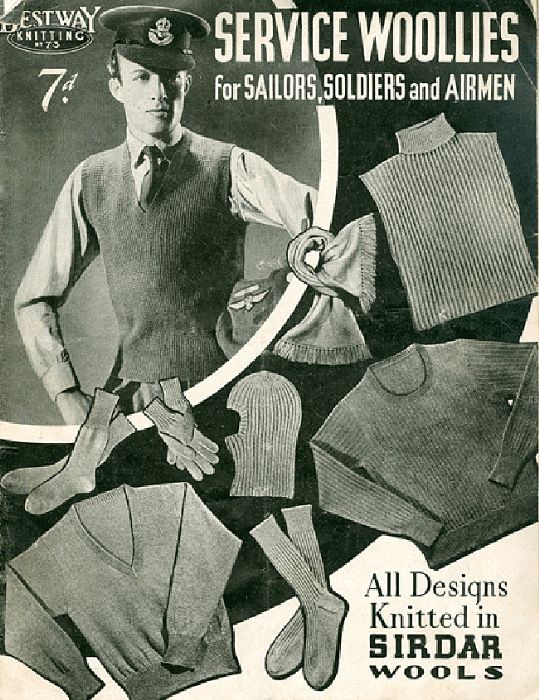

Women in the town knitted socks, scarves, hats and gloves to be distributed among the armed forces known as The Comfort Fund. Women held whist drives to raise money for wool. Many disliked knitting jumpers for the Navy because the wool was waterproofed with oil and was difficult to knit with. In 1943 one lady in Gatehouse knitted 104 pairs of socks and 30 jerseys to be sent to the Forces. There were also various special schemes to raise money to provide kit for a plane or a ship which was often named after the town or area from where the funds came. There was a nationwide scheme to raise money by inviting ladies called Katherine or variations of the name to donate to the "Kat's Spitfire Fund". In 1941 Mrs Katherine McCulloch, of Ardwall contributed £300 to the fund. |

|

Servicemen who went to the Far East were away from home for long periods and communication with their familiies back in Gatehouse was very important. Here is a small sample of the letters and postcards that were written.

British Double Summer time (BDST)In the Autumn of 1940 the clocks were not 'put back' an hour as was the usual practice, so British time remained at Greenwich Mean Time +1 hour (GMT +1) In Spring 1941 the clocks were 'put forward' 1 hour as usual, so now British time was GMT +2. (British Double Summer Time) This put Britain on the same time zone as northern Europe, and it remained in place until the end of summer 1947. There were several reasons behind 'double summertime'

This was not universally popular, particularly in Scotland, where in winter it was dark until well into the morning. Many children had to travel to school in the dark. |

|

This term was used by the British press to describe the sustained German bombing campaign against British cities such as Glasgow, Liverpool and London between September 1940 and May 1941.

A number of Gatehouse folk experienced these events.

|

Archie MacInnes left Gatehouse in 1937 to train as an engineer at Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company at Greenock on the River Clyde. At the outbreak of war he applied to join the REME (Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers) but this was turned down because building ships was more important and he was employed building cruisers, destroyers and submarines for the Royal Navy. Scotts shipyard did receive a direct hit in May 1941 when the main office and drawing office were destroyed. Archie was a member of the Greenock Home Guard and was a member of the anti aircraft battery doing many night duties. For more info about Archie see ‘Kenspeckle Folk’ |

|

Arthur Hunter, joiner, was posted to Liverpool to work refitting troop ships. He was engaged to Nancy Wyse from Glasgow but was not allowed leave to go back to Scotland for his wedding. Instead, Nancy, her father Angus and sister Meg travelled to Liverpool for a small wedding on 26th August 1940.

While the couple were on a short honeymoon, the bombing raids on Liverpool started. The couple lived in Bootle, very close to the docks - a target for the German bombers. Luckily their house survived but the chemist shop where they had taken their wedding photos to be developed was hit and all their wedding photos were lost.

Between August and Christmas 1940, Liverpool was attacked by bombers on average once every other night. It was the most bombed city outside London. Nancy and Arthur took their turns as Fire Watchers. They were equipped with a whistle, a bucket of sand and a stirrup pump. They were tasked with watching for and putting out the fires created from small incendiary bombs which fell in large numbers.

|

|

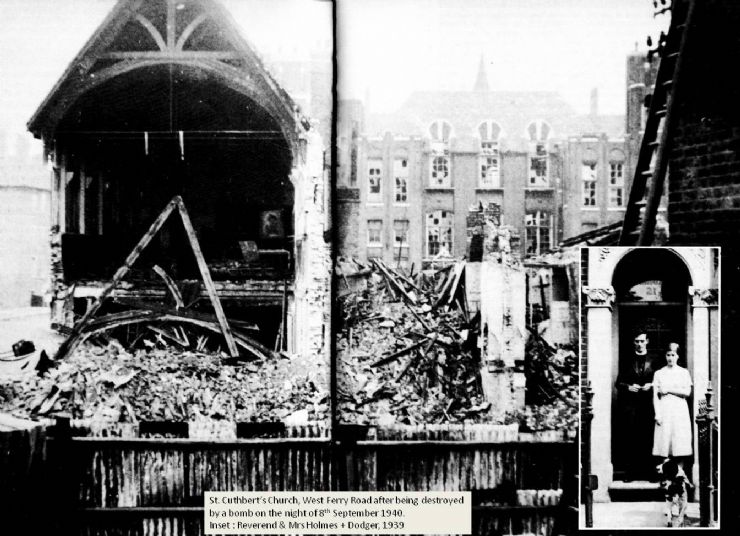

Local girl Rita McMurray met Rev Arthur Holmes while working in the Western Isles. Arthur was an Episcopal minister covering a huge area and used a small plane to travel between the islands - hence his nickname 'the Flying Vicar'. Rita and Arthur married in Gatehouse in 1938. In September 1940 when they were based in London, their church was completely destroyed. After this Arthur became chaplain for the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and served in the Far East. Rita who was pregnant, was evacuated to Oxfordshire and then the Isle of Man, where her daughter Mary was born. |

.jpg)